Content Warning: This article discusses trauma, dissociation, and mental health topics. Please take care of yourself while reading and consider having grounding resources available.

If it feels too much, please, take a break.

Quick Grounding Exercise: Before we begin, take three deep breaths. Feel your feet on the floor, notice five things you can see around you, and remind yourself that you are safe in this moment.

Disclaimer: This article contains information about dissociation and related mental health topics. While we strive for accuracy and base our content on current research, this information should not replace professional medical advice. If you’re experiencing distress, please consult a qualified mental health professional.

Table of Contents

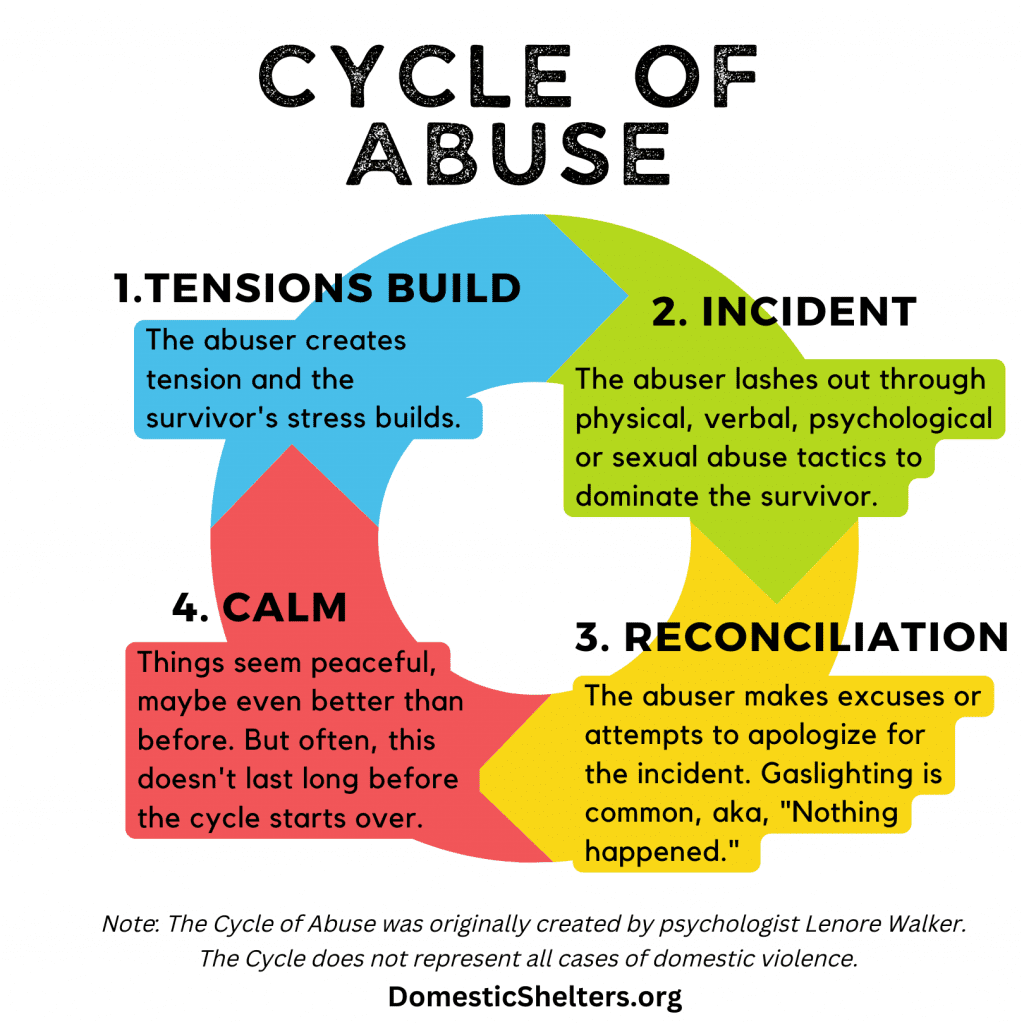

What is the Cycle of Abuse?

The cycle of abuse is a pattern first identified by psychologist Dr. Lenore Walker in 1979 through her research with domestic violence survivors. This cycle helps explain why people in abusive relationships often struggle to leave, why they may return to abusive partners, and why the trauma bonding in these relationships can be so powerful (Walker, 2017).

Understanding this cycle is crucial because it reveals that abuse is not random or spontaneous—it’s a calculated pattern of behavior designed to maintain control. The cycle creates psychological conditions that make leaving extremely difficult, even when the victim logically knows the relationship is harmful (Dutton & Painter, 1993).

It’s important to note that not every abusive relationship follows this exact pattern, and the cycle can vary in length and intensity. Some relationships may skip certain phases, while others may have multiple mini-cycles within larger patterns. However, the general framework helps survivors and supporters understand the complex dynamics at play (Herman, 2015).

The cycle also explains why well-meaning friends and family members often struggle to understand why someone doesn’t “just leave” an abusive relationship. The reality is far more complex than it appears from the outside.

Phase 1: Tension Building

The Atmosphere Changes

The tension building phase is characterized by an increasingly tense and stressful atmosphere. The abuser becomes more irritable, critical, and unpredictable. Small incidents may occur, but the victim often feels like they’re “walking on eggshells,” trying to prevent a major explosive episode (Bancroft, 2002).

During this phase, the victim may notice:

- Their partner becoming increasingly moody or withdrawn

- Minor criticisms or put-downs becoming more frequent

- Feeling constantly anxious about saying or doing the wrong thing

- Hypervigilance—constantly monitoring their partner’s mood and reactions

- Taking on more responsibility to try to prevent conflict

The Victim’s Response

During tension building, victims often develop hypervigilant behaviors and coping strategies:

Appeasement Behaviors: Trying to keep the peace by agreeing, apologizing, or changing their behavior to avoid triggering the abuser

Hypervigilance: Constantly monitoring the abuser’s mood, body language, and verbal cues to predict and prevent explosive episodes

Self-Blame: Taking responsibility for the tension, believing that if they could just be “better,” the problems would stop

Isolation: Avoiding social situations or activities that might upset the abuser or provide outside perspective

Warning Signs During Tension Building

- Increased criticism or nitpicking about small things

- Silent treatment or emotional withdrawal

- Verbal threats or intimidation

- Destruction of property or punching walls

- Increased jealousy or accusations

- Control over daily activities becoming more strict

- Sleep disturbances for both partners

- Increased use of alcohol or substances by the abuser

The duration of this phase can vary dramatically—from hours to months—and tends to shorten over time as the abuse escalates (Walker, 2017).

Phase 2: The Incident

The Explosion Occurs

The acute incident phase is when the abuser releases the built-up tension through an abusive episode. This can involve physical violence, sexual assault, extreme emotional or psychological abuse, or a combination of these (Stark, 2019).

Types of Acute Incidents:

- Physical violence (hitting, choking, restraining)

- Sexual abuse or coercion

- Extreme verbal abuse, screaming, or threats

- Destruction of property or possessions

- Threats against children, pets, or loved ones

- Complete emotional devastation through psychological manipulation

The Victim’s Survival Response

During the acute incident, the victim’s primary focus shifts to survival. This activates the body’s natural trauma responses (van der Kolk, 2014):

Fight Response: Attempting to defend themselves or fight back, though this often escalates the violence

Flight Response: Trying to escape or leave the situation, which may not always be possible

Freeze Response: Becoming paralyzed or unable to move, which is a common and normal trauma response

Fawn Response: Attempting to please or placate the abuser to minimize harm

Psychological Impact of Acute Incidents

The intense fear and helplessness experienced during these episodes creates lasting psychological imprints:

- Trauma Memories: The brain may fragment the experience, making it difficult to remember clearly

- Hyperarousal: The nervous system becomes flooded with stress hormones

- Dissociation: The mind may disconnect from the body as a protective mechanism

- Learned Helplessness: Repeated episodes can create a sense that resistance is futile

The unpredictability of when these incidents occur creates chronic stress and anxiety that persists even during calmer periods.

Phase 3: Reconciliation

The Apology and Promise Pattern

After the acute incident, the abuser typically engages in reconciliation behaviors designed to repair the relationship and prevent the victim from leaving. This phase is often called the “honeymoon phase” because it can feel like a return to the early days of the relationship (Dutton & Painter, 1993).

Common Reconciliation Behaviors:

- Profuse apologies and expressions of remorse

- Promises to change or never hurt them again

- Blame shifting to external factors (stress, alcohol, work pressure)

- Love bombing—excessive attention, gifts, and affection

- Seeking therapy or anger management (often short-lived)

- Involving others to advocate for them (family, friends, religious leaders)

Why This Phase is So Powerful

The reconciliation phase is psychologically devastating because it provides exactly what the victim has been desperately hoping for—acknowledgment of the harm, remorse, and promises of change. This creates several powerful psychological effects:

Intermittent Reinforcement: Like a gambling addiction, the unpredictable rewards (kindness after cruelty) create powerful psychological bonds

Cognitive Dissonance Relief: The apologies temporarily resolve the mental conflict between loving someone who hurts you

Hope Restoration: The promises of change reignite hope that the relationship can work

Trauma Bonding: The cycle of pain followed by relief creates neurochemical bonds similar to addiction

The Victim’s Experience

During reconciliation, victims often experience:

- Relief that the acute episode is over

- Hope that things will really change this time

- Guilt for considering leaving someone who seems genuinely sorry

- Confusion about their own perceptions of the abuse

- Pressure from others who see the abuser’s “reformed” behavior

- Fear that this kindness won’t last

Many victims report that this phase feels like “getting their partner back”—the person they fell in love with before the abuse began.

Phase 4: Calm

The Illusion of Normal

During the calm phase, the abuse temporarily stops, and the relationship may feel relatively normal or even good. The abuser acts as if the previous incident never happened, and there may be periods of genuine happiness and connection (Walker, 2017).

Characteristics of the Calm Phase:

- Absence of acute abusive behavior

- Return to normal daily routines

- Possible increased intimacy or closeness

- The abuser may be especially helpful or attentive

- Family and friends may see the “good side” of the abuser

- The victim may begin to doubt their memories of the abuse

The Psychological Trap

This phase is particularly insidious because it:

Normalizes the Abuse: The victim may begin to think the abuse was an aberration rather than a pattern

Creates False Security: The peace feels so good after the chaos that the victim may lower their guard

Provides Evidence for Denial: Both victim and abuser can point to this phase as proof that “things are fine”

Reinforces Hope: The calm periods “prove” that the abuser can be loving and kind

Confuses Outside Observers: Friends and family may see the calm phase and question the victim’s reports of abuse

The Gradual Return to Tension

The calm phase inevitably deteriorates as the abuser’s need for control reasserts itself. The victim may notice:

- Small irritations beginning to surface

- Subtle criticisms or controlling behaviors returning

- Feeling increasingly anxious about maintaining the peace

- Walking on eggshells becoming a familiar feeling again

Variations and Modern Understanding of the Cycle

Not All Abuse Follows This Pattern

While the cycle of abuse is a valuable framework, it’s important to understand its limitations:

Some relationships have constant tension with no clear calm periods

Others may have very brief cycles that happen multiple times in a day

Certain types of abuse (like coercive control) may be more constant and less cyclical

The cycle can change over time, often with shorter calm periods and more frequent acute incidents

Technology and Modern Abuse Cycles

Digital technology has added new dimensions to the abuse cycle:

Constant Contact: Smartphones allow for continuous monitoring and harassment Digital Honeymoon: Social media can be used for public displays of affection during reconciliation Online Surveillance: Technology enables new forms of control and intimidation Digital Evidence: Text messages and social media posts can document the cycle more clearly

Economic and Social Factors

The cycle intersects with practical realities that make leaving difficult:

Financial Dependency: Economic abuse often traps victims regardless of the cycle phase Social Isolation: The abuser systematically removes support systems that could help break the cycle Children and Custody: Concerns about children’s safety and custody arrangements complicate leaving Housing and Legal Issues: Practical barriers to leaving persist throughout all phases of the cycle

/image <Add an infographic showing how external factors (financial, social, legal) intersect with the abuse cycle>

Why the Cycle Makes Leaving So Difficult

Trauma Bonding Explained

The cycle of abuse creates what researchers call “trauma bonding”—powerful emotional attachments formed through cycles of abuse and relief. This creates several psychological conditions that make leaving extremely difficult (Dutton & Painter, 1993):

Biochemical Addiction: The stress hormones followed by relief hormones create an addictive cycle similar to substance abuse

Identity Fusion: The victim’s sense of self becomes intertwined with the relationship and the abuser’s needs

Learned Helplessness: Repeated failed attempts to change the situation lead to giving up

Cognitive Dissonance: The mind struggles to reconcile love with abuse, often resolving this by minimizing the abuse

The Hope Factor

Each honeymoon phase provides evidence that change is possible, making it rational to hope that “this time will be different.” This hope is reinforced by:

- Genuine moments of connection and love

- Promises that seem sincere

- Small changes that suggest improvement

- Social pressure to “work on the relationship”

- Religious or cultural beliefs about commitment

External Pressures

Society often doesn’t understand the cycle, leading to:

- Victim blaming (“Why don’t you just leave?”)

- Minimization of abuse during calm periods

- Pressure to “give them another chance”

- Lack of support for multiple leaving attempts

- Economic and legal barriers to independence

Breaking Free from the Cycle

Recognizing the Pattern

The first step in breaking free is recognizing the cycle in your own experience:

Keep a Journal: Document incidents, feelings, and patterns over time

Track Your Emotions: Notice how you feel in different phases

Identify Triggers: What typically precedes the tension building phase?

Notice Your Responses: How do you adapt your behavior in each phase?

Seek Outside Perspective: Trusted friends, family, or professionals can help you see patterns

Safety Planning Across All Phases

Different phases require different safety strategies:

During Tension Building:

- Have a safety plan ready

- Keep important documents accessible

- Maintain contact with support people

- Trust your instincts about escalating danger

During Acute Incidents:

- Prioritize physical safety over property

- Know your escape routes

- Have emergency contacts readily available

- Remember that surviving is the priority

During Reconciliation:

- Resist the urge to make major decisions

- Remember the pattern, not just the current moment

- Maintain connections with support people

- Document promises made and broken

During Calm Phases:

- Use this time to strengthen your support network

- Plan for future safety

- Consider professional help

- Remember that this phase is temporary

Professional Support

Breaking the cycle often requires professional help:

Domestic Violence Advocates: Specialists who understand the cycle and can help with safety planning

Trauma-Informed Therapists: Mental health professionals trained in abuse dynamics

Legal Advocates: Help with restraining orders, custody issues, and other legal protections

Support Groups: Connect with others who understand the cycle firsthand

Simplified Version for Difficult Moments: If you’re in a relationship that follows this pattern of tension, explosion, apology, and calm, you are not imagining things. This is a recognized pattern of abuse, and you deserve help and support to stay safe.

Healing After Breaking the Cycle

Understanding Post-Cycle Recovery

Even after leaving an abusive relationship, survivors may continue to experience effects of the cycle:

Hypervigilance: Remaining constantly alert for signs of danger or tension Anniversary Reactions: Emotional responses triggered by dates or situations that remind you of abuse Cognitive Dissonance: Continuing to struggle with conflicting feelings about the abuser Trauma Bonding Withdrawal: Missing the abuser despite knowing the relationship was harmful

Rebuilding After the Cycle

Recovery involves developing new patterns to replace the destructive cycle:

Stable Relationships: Learning what healthy, consistent relationships look like Emotional Regulation: Developing skills to manage intense emotions without crisis Trust in Perception: Rebuilding confidence in your own reality and judgment Self-Compassion: Healing the self-blame and shame created by the cycle

Grounding Exercise for Now

Take a moment to notice: Are you safe right now? Feel your body in your chair, your feet on the floor. Take three deep breaths and remind yourself that you are learning about these patterns to protect and empower yourself. You are brave for seeking this knowledge.

References

- Bancroft, L. (2002). Why Does He Do That? Inside the Minds of Angry and Controlling Men. Berkley Books.

- Dutton, D. G., & Painter, S. (1993). Emotional attachments in abusive relationships: A test of traumatic bonding theory. Violence and Victims, 8(2), 105-120.

- Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and Recovery. Basic Books.

- Stark, E. (2019). Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life. Oxford University Press.

- van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin Books.

- Walker, L. E. (2017). The Battered Woman Syndrome. Springer Publishing.