Content Warning: This article discusses trauma, dissociation, and mental health topics. Please take care of yourself while reading and consider having grounding resources available.

If it feels too much, please, take a break.

Quick Grounding Exercise: Before we begin, take three deep breaths. Feel your feet on the floor, notice five things you can see around you, and remind yourself that you are safe in this moment.

Disclaimer: This article contains information about dissociation and related mental health topics. While we strive for accuracy and base our content on current research, this information should not replace professional medical advice. If you’re experiencing distress, please consult a qualified mental health professional.

Normal, Everyday Dissociation

Common Non-Pathological Experiences

We may all find ourselves on the lower end of the dissociation spectrum, here are a few common examples:

Highway Hypnosis: Driving a familiar route and suddenly realizing you don’t remember the last several miles, yet you arrived safely

Absorption in Activities: Becoming so engrossed in a book, movie, or video game that you lose awareness of your surroundings or the passage of time

Daydreaming: Letting your mind wander during boring tasks or conversations, creating mental scenarios or planning future events

Most people experience dissociation regularly without realizing it. These everyday experiences are completely normal and typically don’t interfere with functioning (Butler, 2006)

Flow States: Becoming completely absorbed in creative or athletic activities where time seems to stop and self-consciousness disappears

Automatic Behaviors: Performing routine tasks like brushing teeth or walking to work while your mind is elsewhere

Meditation and Prayer: Intentional altered states of consciousness during spiritual practices

Characteristics of Normal Dissociation

Everyday dissociation typically has several characteristics that distinguish it from problematic dissociation:

- Voluntary Control: You can usually redirect your attention when needed

- No Distress: These experiences don’t cause anxiety or concern

- Functional: They don’t interfere with daily activities or relationships

- Brief Duration: They last for relatively short periods

- Contextual: They occur in specific, usually safe situations

- Reversible: You can easily return to normal awareness

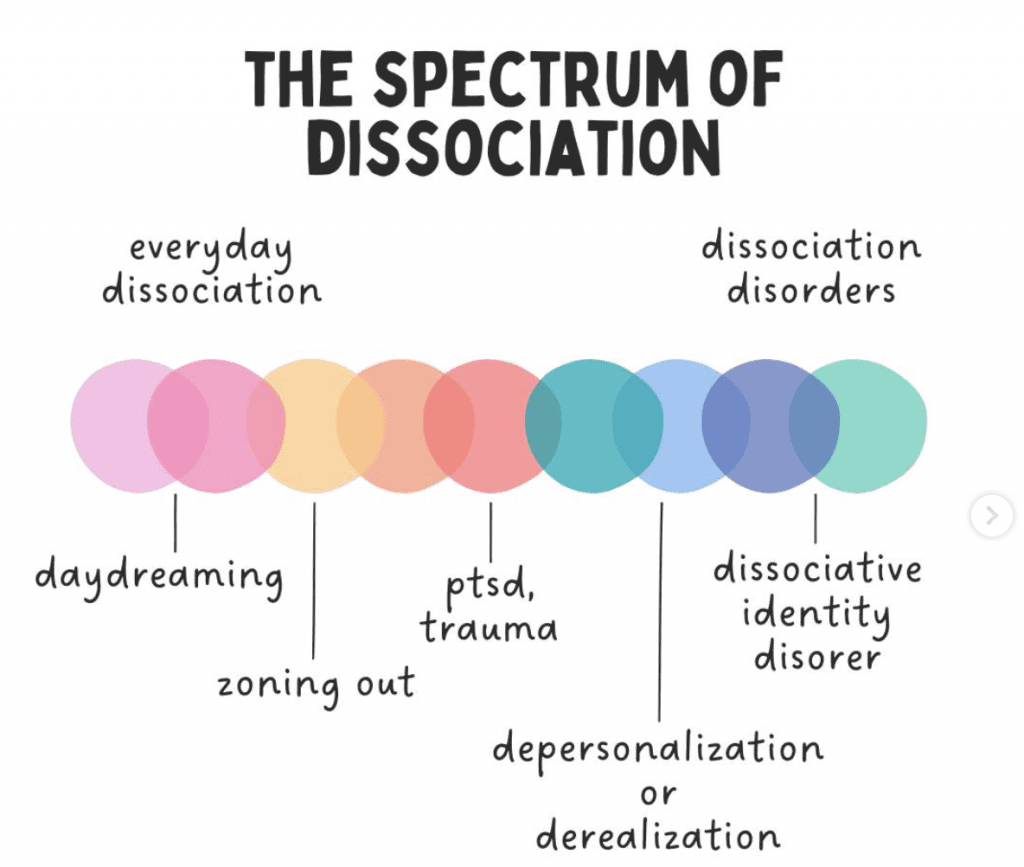

What is the Dissociation Spectrum?

Dissociation exists on a spectrum—a continuum of experiences ranging from completely normal, everyday occurrences to more significant disconnections that may indicate trauma or mental health concerns. Understanding this spectrum is crucial because it helps normalize common experiences while also recognizing when dissociation may be a sign that someone needs support (Putnam, 1997).

At its core, dissociation involves a disconnection or separation between thoughts, feelings, memories, or sense of identity that would normally be integrated. Rather than being a binary experience—either present or absent—dissociation manifests in varying degrees of intensity and frequency (Steinberg & Schnall, 2000).

The spectrum approach helps us understand that not all dissociative experiences are pathological or concerning. Many people experience mild forms of dissociation regularly without any negative impact on their lives. However, when dissociation becomes frequent, intense, or interferes with daily functioning, it may indicate underlying trauma or other mental health conditions (Brand et al., 2016).

This understanding is particularly important for trauma survivors, who may experience shame or confusion about their dissociative experiences. Recognizing dissociation as a spectrum helps normalize these experiences while also providing a framework for understanding when professional support might be beneficial.

Mild to Moderate Dissociation

When Dissociation Becomes More Noticeable

As we move along the spectrum, dissociative experiences become more frequent, intense, or noticeable, though they may still fall within the range of normal variation (Dell & O’Neil, 2009):

Frequent Spacing Out: Regular episodes of losing awareness during conversations or activities

Time Loss: Missing larger chunks of time or having difficulty accounting for periods of the day

Emotional Numbing: Feeling disconnected from emotions or experiencing them as distant

Physical Disconnection: Feeling detached from your body or like you’re observing yourself from outside

Memory Gaps: Difficulty remembering conversations, events, or activities that recently occurred

Identity Confusion: Occasional uncertainty about who you are or feeling like different versions of yourself

Stress-Related Dissociation

Many people experience increased dissociation during periods of stress, which can be a normal coping mechanism:

- Academic Stress: Students may dissociate during exams or high-pressure situations

- Work Pressure: Employees might “check out” mentally during overwhelming workdays

- Relationship Conflicts: Some people dissociate during arguments or emotional confrontations

- Life Transitions: Major changes like moving, job changes, or relationship changes can trigger increased dissociation

Moderate to Severe Dissociation

Clinical Significance

As dissociation becomes more severe, it begins to significantly impact daily functioning and may indicate underlying trauma or mental health conditions (Carlson & Putnam, 1993):

Significant Time Loss: Missing hours or entire days with no memory of activities

Amnesia for Important Events: Inability to remember significant personal experiences

Identity Alteration: Feeling like different people at different times or having distinct personality states

Severe Depersonalization: Persistent feelings of being detached from yourself or your body

Severe Derealization: Ongoing feelings that the world around you is unreal or dreamlike

Functional Impairment: Dissociation interferes with work, relationships, or daily activities

Trauma-Related Dissociation

Moderate to severe dissociation is often linked to trauma exposure, particularly childhood trauma or complex trauma (van der Hart et al., 2006):

- Protective Function: The mind uses dissociation to protect consciousness from overwhelming experiences

- Learned Response: Dissociation becomes an automatic response to stress or trauma reminders

- Fragmented Memories: Traumatic experiences may be stored in disconnected fragments

- Emotional Disconnection: Feelings associated with trauma may be split off from conscious awareness

You can read more about the different types of trauma and their impact here.

Dissociative Disorders on the Spectrum

Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder

This disorder involves persistent or recurrent experiences of feeling detached from oneself (depersonalization) or feeling that the world is unreal (derealization) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022):

- Prevalence: Affects approximately 2% of the population

- Characteristics: Chronic feelings of detachment that cause significant distress

- Functioning: May maintain awareness that these feelings aren’t “real” but still experience distress

- Triggers: Often triggered by stress, trauma, or substance use

Dissociative Amnesia

Characterized by inability to remember important personal information, usually related to trauma or stress:

- Localized Amnesia: Forgetting a specific traumatic event or period

- Selective Amnesia: Remembering some but not all aspects of a traumatic period

- Generalized Amnesia: Forgetting entire life history (rare)

- Systematized Amnesia: Forgetting specific categories of information

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID)

Previously known as Multiple Personality Disorder, DID involves the presence of two or more distinct personality states:

- Distinct Identities: Each with its own patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving

- Amnesia: Memory gaps between different identity states

- Distress or Impairment: Significant impact on daily functioning

- Trauma History: Usually associated with severe childhood trauma

For a comprehensive understanding of this condition, read our detailed guide on Dissociative Identity Disorder.

Other Specified Dissociative Disorder (OSDD)

Formerly called Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (DDNOS), this category includes:

- OSDD-1a: Similar to DID but without distinct identities

- OSDD-1b: Similar to DID but without significant amnesia between parts

- Other Presentations: Various other clinically significant dissociative symptoms

Factors That Influence Where Someone Falls on the Spectrum

Trauma History

The severity, frequency, and timing of trauma significantly influence dissociative experiences (Putnam, 1997):

- Early Childhood Trauma: Trauma occurring during critical developmental periods often leads to more severe dissociation

- Complex Trauma: Repeated, ongoing trauma typically results in more complex dissociative responses

- Severity of Trauma: More severe trauma generally correlates with more severe dissociation

- Attachment Trauma: Trauma within caregiver relationships particularly affects dissociative responses

Individual Factors

Personal characteristics influence dissociative capacity and responses:

- Hypnotizability: Natural ability to enter trance states correlates with dissociative capacity

- Fantasy Proneness: Tendency toward imagination and fantasy relates to dissociative experiences

- Absorption: Ability to become deeply focused or absorbed in activities

- Genetic Factors: Some research suggests genetic predisposition to dissociative responses

Adaptive vs. Maladaptive Dissociation

When Dissociation is Protective

Dissociation often serves important adaptive functions, particularly in response to trauma (Kluft, 2006):

- Survival Mechanism: Allows consciousness to escape when physical escape isn’t possible

- Emotional Protection: Shields awareness from overwhelming emotions or experiences

- Functional Preservation: Enables some aspects of life to continue despite trauma

- Developmental Adaptation: Helps children cope with adverse environments

When Dissociation Becomes Problematic

Dissociation becomes maladaptive when it:

- Persists After Safety: Continues in safe environments where it’s no longer needed

- Interferes with Functioning: Prevents engagement in work, relationships, or daily activities

- Prevents Processing: Blocks integration of experiences necessary for healing

- Increases Vulnerability: Creates safety risks or prevents appropriate responses to danger

Simplified Version for Difficult Moments: Dissociation exists on a spectrum from normal everyday experiences (like getting absorbed in a book) to more significant disconnections that may need support. Where you are on this spectrum can change over time, and movement toward the healthier end is possible with support and healing.

Moving Along the Spectrum: Recovery and Integration

Understanding Recovery

Recovery from dissociative experiences is often about moving toward the healthier end of the spectrum rather than eliminating dissociation entirely:

- Integration: Learning to connect disconnected aspects of experience

- Grounding: Developing skills to stay present and connected

- Safety: Creating internal and external safety to reduce need for dissociation

- Processing: Working through traumatic experiences in manageable ways

Therapeutic Approaches

Various therapeutic approaches can help people move toward healthier dissociative experiences:

- Trauma-Focused Therapy: Addressing underlying trauma that triggers dissociation

- Grounding Techniques: Learning skills to stay present and connected

- Internal Family Systems: Working with different aspects of self in a healing way

- Somatic Approaches: Reconnecting with the body and physical sensations

- EMDR: Processing traumatic memories to reduce dissociative triggers

You can read more about our recommended Grouding Techniques here.

Grounding Exercise

Take a moment to check in with yourself right now. How are you feeling after learning about these different experiences? Remember that wherever you are on the dissociation spectrum, you deserve understanding, compassion, and support on your healing journey.

Further Reading & Recommended Books

For Understanding Dissociation

The Stranger in the Mirror by Marlene Steinberg

Comprehensive guide to understanding the full spectrum of dissociative experiences from mild to severe.

The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk

Understanding trauma’s impact including dissociative responses and evidence-based healing approaches.

For Healing and Coping

Coping with Trauma-Related Dissociation by Suzette Boon, Kathy Steele, and Onno van der Hart

Practical skills for managing dissociative symptoms across the spectrum with compassionate guidance.

References & Sources

- Brand, B. L., Sar, V., Stavropoulos, P., Krüger, C., Korzekwa, M., Martínez-Taboas, A., & Middleton, W.

(2016).

Separating fact from fiction: An empirical examination of six myths about dissociative identity disorder.

Harvard Review of Psychiatry,

24(4),

257-270.

DOI: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000100 - Butler, L. D.

(2006).

Normative dissociation.

Psychiatric Clinics of North America,

29(1),

45-62.

DOI: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.006 - Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W.

(1993).

An update on the Dissociative Experiences Scale.

Dissociation,

6(1),

16-27.

Available here - Dell, P. F., & O’Neil, J. A. (Eds.).

(2009).

Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders.

Routledge.

Available here - Kluft, R. P.

(2006).

Dealing with alters: A pragmatic clinical perspective.

Psychiatric Clinics of North America,

29(1),

281-304.

DOI: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.010 - Putnam, F. W.

(1997).

Dissociation in Children and Adolescents.

Guilford Press.

Available here - Steinberg, M., & Schnall, M.

(2000).

The Stranger in the Mirror.

HarperCollins.

Available here - van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R., & Steele, K.

(2006).

The Haunted Self.

W. W. Norton & Company.

Available here